Silver Dollars & Trade Dollars of the United States - A Complete Encyclopedia

Q. David Bowers

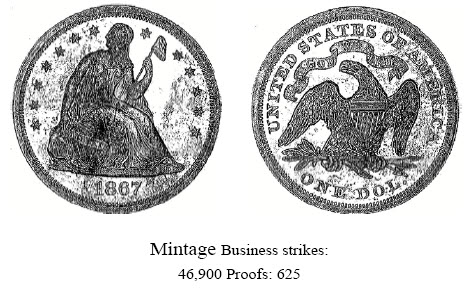

1867 Liberty Seated Dollar

Coinage Context

Distribution: Export use consumed many if not most of the Liberty Seated dollars minted this year. The trade with the Orient was active once again, and it is believed that many were shipped there. In the meantime, all was not well with the Mexican silver dollar in its use in China. In 1866 the familiar cap and rays design, in use for generations, was briefly abandoned in favor of a new and quite different style portraying Emperor Maximilian, whose reign would be short-lived (see Additional Information below).

Tradition was a key factor in the acceptance of gold and silver trade coins in all parts of the world, and for this reason the famous Maria Theresa silver taler of Levant, dated 1780, was minted in essentially unchanged form for the next two centuries. So it was with the Mexican dollar; Chinese merchants did not trust the new Maximilian coins. These new and unfamiliar pieces caused confusion with Chinese bankers and others, who were not sure how to value them and who did not consider them as secure as the old design. (Willem, The United States Trade Dollar, pp. 50-51.) As if this was not bad enough for the fortunes of the Mexican silver dollar, the country of Mexico slapped a tax of about 12% on the export of its silver coins, in order to finance an internal program of education.

The result was that after 1866, there was an opportunity waiting to be filled. American exporters did not wait long to resume shipping Liberty Seated dollars to China, where, considering the new tax on Mexican dollars, they could be competitive. This was not the perfect answer, for the Mexican dollars remained of a heavier standard, but the red tape and taxes at the Mexican end benefited the Americans. Willem writes that this was the primary reason for substantially larger mintages of Liberty Seated dollars of the 1869-1873 years.

Numismatic Information

Circulated grades: The year 1867 is particularly elusive among Liberty Seated dollars in business strike form, and relatively few exist. Dr. John W. McCloskey has written: "The 1867 dollar is very rare and underrated in all circulated grades and is possibly the rarest of the Philadelphia Mint with-motto dates. ("An 1867 Dollar With Recut Date," The Gobrecht Joumal; November 1982. In a letter to the author, April 28, 1992, Dale R. Phelan suggested that no more than 200 business strikes exist.)

The only reason that a nice EF-40 coin does not catalogue for well over $1,000 is that Proofs come on the market often enough to satisfy advanced collectors' demand for this date. Likewise, the availability of Proofs has held down the prices of all other Liberty Seated dollars after 1858.

Mint State grades: The year 1867 is a remarkable one in the coinage of United States silver issues, as with the exception of the half dollar all denominations are rarities. Among American silver coins this. date has always had a special numismatic popularity, as does the year 1877 in the bronze and nickel series. The 1867 dollar is very elusive in Mint State and is particularly so in grades of MS-64 or higher.

On some high-grade specimens extensive die striae, as struck, are seen on the obverse; reverse with many unfinished areas within shield stripes. Most high-grade coins are prooflike.

1867 Proofs: The 625 Proof dollars of this year were struck from at least three different obverse dies, extraordinary for a low mintage. One of these, the blundered date (large date over small date, No. 4, below) was first discovered by Walter H. Breen in the 1970s and remains rare, although relatively unpublicized, today.

Proof silver dollars of 1867 were distributed with the silver Proof sets of the year.

Varieties

Business strikes:

1. Normal Date: Breen-5477. Date well centered in field.

2. Large over Small Date: Obverse: The die used to coin Proof No.4 (below), but worn. Only traces of the blunder remain. Walter H. Breen knew of only two specimens as of February 1992; one of these was owned by Maurice Rose. (Letter from Walter H. Breen to the author, February 12,1992. Maurice Rose, a West Coast dealer, is not to be confused with Maurice Rosen, the well-known New York professional numismatist.) The author examined another coin, certified by PCGS as MS-60, in the Robert P. Guardiano Collection, in September 1992. This variety probably formed only a tiny part of the 10,300 delivered on November 22nd.

Proofs:

1. Proof issue: Breen-5477. Obverse: Date high. Shield point slightly to the right of the tip of 1 in date. Border denticles normal (not undersized). Reverse: Same as that used to coin Nos. 2 and 3 of 1866 with motto. The five known strikings in brass came from this die combination.

2. Proof issue: Breen-5477. Obverse: Date high. Shield point midway between the tip and upright of 1 in date. Border denticles between 12 o'clock and 2 o'clock on border smaller than usual and spaced farther apart, from die lapping. Reverse: As preceding, but now repolished. Apparently, this die combination is the most often seen of 1867.

3. Proof issue: Breen-5477. Obverse of No.2 above. Reverse: Die also used in 1868, with spine joining arrowhead and inner angle of L in DOL. This die reappears on No.4 (below), 1868 No.1, and 1869 No. 1 Proofs. Apparently, relatively few Proofs were struck from this combination in 1867.

4. Proof issue; Large Date Over Small Date:

Breen-5478. Obverse: Blundered date; 1867 over smaller date. Apparently, a logotype for a half dollar was erroneously applied to the blank die, high and slanting down to the right. Then, the regular dollar logotype was punched in the correct position. The early state (rarest) shows much of the small date; later states (slightly less rare) show less, finally only traces. Apparently, die lapping obscured the blunder. This obverse was later used for business strike No.2, which see. Reverse: Die of No.3, now repolished at the ribbon. Walter H. Breen suggests that these may have been part of the 100 pieces struck in June 1867.