Silver Dollars & Trade Dollars of the United States - A Complete Encyclopedia

Q. David Bowers

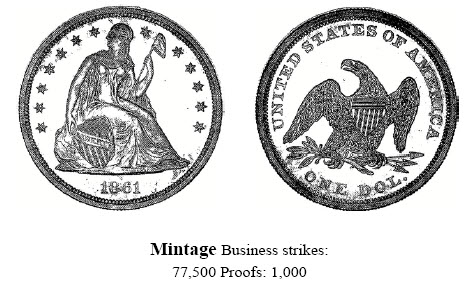

1861 Liberty Seated Dollar

Coinage Context

Status of the dollar: After spring 1853 the silver dollar no longer circulated at par as it had a bullion value greater than its face value. In his 1861 Annual Report of the Director of the Mint (quoted at length below) James Pollock said that he sold silver dollars in small lots at 108 cents, specifically:

The silver dollar, as it now is, actually has three values:

1. It is a dollar simply, or 100 units or cents;

2. By the Mint price of silver it is 103-948/1000 cents, which is its true commercial value as compared with gold.

3. It has an interior, or Mint value, which is determined by its relation to silver in the half dollar, which makes it 107-27/ 64 cents, for which reason single pieces are paid out at the Mint, at the even price of 108 cents.

After early 1853, and continuing to at least 1860, the vast majority of Liberty Seated dollars were shipped to Chinese ports, where they were used to pay for merchandise. They were not an advantageous trade coin for American exporters who had to buy them at a premium from banks and bullion dealers, and once they reached China they sold at a discount in comparison to the heavier Mexican silver dollars. For this reason, the United States made special trade dollars of heavier weight beginning in 1873.

As Liberty Seated dollars were accepted by the Chinese by weight, not by sight, few were counter-stamped for further use. Rather, most were shipped in bulk to melters and refiners and foreign mints.

A change in emphasis: Beginning in 1861, emphasis in silver dollar distribution was not primarily export to China. Rather, in this year some pieces were sent beyond the borders of the United States, but for the first year in nearly a decade, many remained stateside. R.W. Julian relates that in one instance in 1861 a quantity amounting to 40,000 silver dollars went to the melting pot to provide silver for subsidiary coins.

Numismatic Information

Circulated grades: When it comes to 1861 dollars, rarity is the order of the day. While Proofs are occasionally seen on the market, business strikes in all degrees are very elusive. The relative degree of business strikes of all Philadelphia Mint Liberty Seated dollars of the early 1860s is difficult to calculate. Proofs come on the market with regularity, as noted, but these are more visible than business strikes and tend to be included in auctions more often than VF and EF coins.

The circulated business strikes of the early 1860s furnish an area of intense interest to Liberty Seated specialists, and in my business and research correspondence I receive more inquiries on these than on any others of the design, with the Carson City coins running a close second.

The acquisition of a nice Very Fine, Extremely Fine, or AU 1861 dollar is an occasion for pride. Fortunately, catalogue valuations do not at all reflect the true rarity of such coins, especially in relation to the rarity of later, more publicized higher priced rarities such as the 1893-S Morgan dollar.

Mint State grades: Although the 1861 is very rare in business strike form, it is not in the very top echelon of rarity in Mint State. Still, specimens are rare, and when they come on the market they attract attention, deservedly so. Uncirculated coins, when found, are just as apt to be MS-63 or MS-64 than in a lower Mint State grade.

Quality of striking: Many 1861 business strike dollars show areas of light striking. Indeed, this is a hallmark of this particular date.

Proofs: Although 1,000 Proof 1861 Liberty Seated silver dollars were minted, it is believed that only about 350 were ever sold. Of issues dated in the early 1860s, the 1861 is the rarest Proof today. Single Proof dollars cost $1.60 each at the Mint.

As in 1860, optimism prevailed about the growth of coin collecting, and on April 15, 1861, 1,000 copper-nickel and silver Proof sets were delivered. However, sales languished, and early in 1862 over 600 sets were consigned to the melting pot. These were part of a group of 1,061 silver Proof sets of earlier years, plus extra unidentified Proofs, delivered to the melter and refiner on January 13, 1862. The days were still far distant when dealers such as David Proskey would absorb left-over Proofs at face value or for a small premium. R. W. Julian has written the following on this subject:

A number of 1860 and 1861 Proof sets appear to have been melted (although it cannot be determined at present how many of each date) for on January 13, 1862, the Treasurer sent to the Melter and Refiner 1,061 sets of silver Proofs plus "odd amounts." These 1,061 sets probably contained Proof pieces of dates prior to 1860 because it seems to have been Mint practice (ending with the January 1862, melting?) to sell Proof pieces of a given year for some years afterwards. The melting of the old Proof sets may have represented Mint reaction to criticism. of various numismatic ventures of the officials, such as the 1804 dollars and other restrikings.

Today, 1861 Proof dollars are very elusive. Not only was the distribution low, as noted, but those sold seem to have had an unusually high attrition rate.

Varieties

Business strikes:

1. Arrowheads touch: Breen-5467. Obverse: Apparently the die described below for Proofs. Reverse: With 2nd and 3rd arrowheads touching, as in former years.

2. Arrowheads apart: Obverse: As No. 1. Reverse:

Arrowheads spaced distinctly apart, as in later years. Seven obverse and eight reverse dies were made for 1862; probably most were not used.

Proofs:

1. Proof issue: Breen-5467. Obverse: Date impressed lightly in die, slightly below center between rock base of Miss Liberty and border denticles. Shield point very slightly to the left of the upright of the first 1 in date; base of first 1 right of center of denticle; right base of final 1 left of center of denticle. Reverse: Deeply impressed features in die; arrows nearly touch each other. Small unpolished spot between upper and central pairs of leaves. On later Proof strikes a crack developed from the rim to the period and arrows.

Note: In general, Proof dollars of earlier dates have the 2nd and 3rd arrowheads touching, and later Proofs have them separated. More study is needed to confirm if this represented a hub change or if it was related to the depth impression of the hub into the master die or the working hub into working die.