Commemorative Coins of the United States

Q. David Bowers

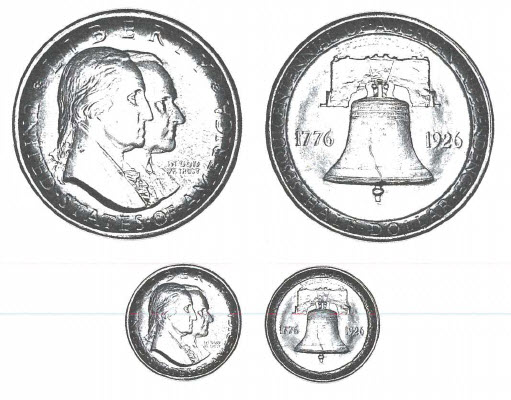

1926 Sesquicentennial of American Independence Half Dollar

Coins for an Exposition

There is no doubt that the 150th anniversary of American independence 1776- 1926 was an event worthy of commemoration on coins. To observe the occasion, Congress on March 23, 1925, a year in advance of the sesquicentennial date, approved a resolution providing for the coinage of not more than one million silver half dollars and not more than 200,000 gold $2.50 pieces. The coins were to be delivered at face value to authorized officers of the National Sesquicentennial Exhibition Association. (Also referred to as the Sesquicentennial Exhibition Association (without National) in the same legislation.) The term exhibition, used in the Original Congressional legislation, was taken from the 1876 Centennial Exhibition held in Philadelphia 50 years earlier. When the 1926 event took place, it was primarily designated as the Sesquicentennial Exposition, although the exhibition word crept into some publicity.

The original bill for the pieces, before emendation, provided for the production of a unique denomination, the $1.50 gold piece, which was later deleted from the request. The Association had also hoped to have an expanded series of coins utilizing designs representing different periods in the growth of the United States-for ex-ample, the original colonies, the Louisiana Purchase, California and Texas accessions, etc. Unfortunately for numismatic posterity, this illustrious series never came to pass.

The Exposition opened in Philadelphia on June 1, 1926, although many exhibits were not yet in place and much work remained unfinished, and continued until closing day on November 30th. On view were many artistic, cultural, scientific, and commercial displays, partially financed by $5 million worth of bonds floated by the City of Philadelphia. The Palace of Agriculture and Food Products and the Palace of Liberal Arts were two of the larger structures.

As it did not attract national attention or support, the fair was a failure so far as commercial activities were concerned, and most firms reported that sales and publicity generated did not repay the expenses involved, although nearly six million people passed through the entrance gates. In the annals of fairs and expositions in the United States, the Sesquicentennial event earns a low rating.

Design and Distribution

John Sinnock, chief engraver at the Mint, was named to create the designs for the two approved commemorative coin denominations, but his proposal for the half dollar was unsatisfactory to the National Sesquicentennial Exhibition Association. Design ideas in the form of sketches submitted by attorney John Frederick Lewis, a prominent local patron of the arts, were accepted and sent to Sinnock for translation to models.

The quarter eagle was created by Sinnock from his own sketches. For years the Mint maintained that Sinnock designed the half dollar as well, a falsehood that found its way into numerous reference books and other printed sources of information. As Don Taxay suggested in his 1967 reference on the commemorative series, "Perhaps .. .it is time for a new credit line." Actually, Lewis and Sinnock should share the credit.

The obverse of the half dollar depicts the conjoined portraits of presidents Washington and Coolidge (Washington possibly because he later became the first president of the United States or possibly because of his connection with the Continental Army, and Coolidge because he happened to be president when the coin was issued). Objections were raised concerning the use of the portrait of a living person on current coinage in the same vein as the complaints made with Governor Kilby's visage on the 1921 Alabama half dollars, but the protest went unheeded. The reverse showed the Liberty Bell, the famous American emblem, which, per the inscription cast into it, was intended to "Proclaim Liberty throughout all the Land unto all the Inhabitants Thereof," from a biblical quotation (Leviticus 25:10).

At the insistence of the Association, the designs were executed in very shallow relief with the result that the pieces struck up poorly.