Commemorative Coins of the United States

Q. David Bowers

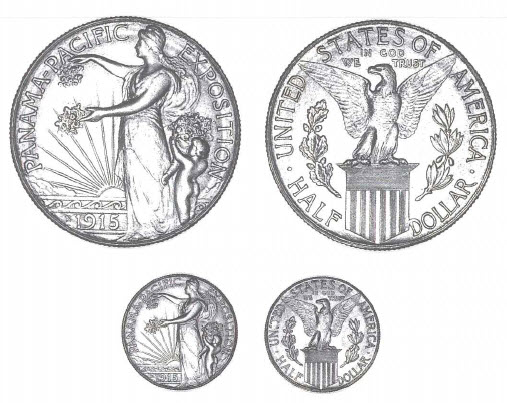

1915-S Panama-Pacific International Exposition Half Dollar

Farran Zerbe

The next silver commemorative coin to be created was the 1915-S half dollar struck in San Francisco in conjunction with the Panama-Pacific International Exposition held in that city in 1915 to celebrate the 1914 completion of the Panama Canal and the rebirth of the Golden Gate City from the 1906 earthquake and fire.

At the urging of numismatic entrepreneur Farran Zerbe a spectacular set of Panama-Pacific commemorative coins was created including a silver half dollar, gold dollar, quarter eagle, and two varieties of $50 pieces. Zerbe, perhaps America's greatest numismatic showman, began his interest in numismatics as a young lad while a newsboy in Tyrone, Pennsylvania. By the turn of the century he had assembled a marvelous collection of numismatic specimens illustrating the entire range of coins, tokens, medals, and paper money. Titled Money of the World, the collection was mounted in frames and display cases and exhibited all across America with an early showing being at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. (Zerbe's Money of the World exhibit was shown in many parts of America, especially in bank lobbies, through the 1920s, after which time it was sold to the Chase National Bank of New York City. It later formed the basis for the Chase Manhattan Money Museum, a popular New York City attraction of the 1950s and 1960s. The museum was subsequently closed, and many of the numismatic items were transferred to the National Collection at the Smithsonian Institution.)

Zerbe was a frequent contributor to The Numismatist, which, together with the American Journal of Numismatics, was one of two publications issued by non-profit coin collecting organizations at the time. (The Numismatist was and still is published monthly by the American Numismatic Association. The American Journal of Numismatics was a quarterly, then an intermittent publication of the American Numismatic Society. and now in its "Second Series," it is an annual.) Zerbe visited the Denver Mint in 1905, reported on its plans for opening, and suggested that the facility incorporate a numismatic museum (the Denver Mint opened in 1906 and did not include a museum). In San Francisco he interviewed mint employees and officers and endeavored to find out about the rare 1894-S dime (of which 24 were said to have been minted) and the mystery surrounding the 1873-S Liberty Seated silver dollar (of which 700 were reported struck but no specimen has ever come to light).

Crisscrossing the United States on several occasions, Zerbe reported to readers of The Numismatist various happenings with dealers and collectors, spicing his observations with personal sketches and interesting opinions. From 1907 to 1909 Zerbe served as president of the American Numismatic Association, an administration tinged with controversy, for some considered Zerbe to be exploitative instead of altruistic in certain of his actions. In an era in which coin collecting was rapidly becoming a popular national pastime, Zerbe did much to further the hobby. Without question, his Money of the World exhibit at fairs, exhibitions, banks, and elsewhere attracted a wide circle of viewers, many of whom became collectors.

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition

By 1915 expositions, some of which were designated as world's fairs, had become part of the American way of life. The 1876 Centennial Exhibition, held in Philadelphia to commemorate the 100th anniversary of American independence, drew millions of visitors and set the stage for the successful World's Columbian Exposition held in 1893 as well as various other events, some large and some small, including the 1898 Trans-Mississippi Exposition in Omaha, the 1901 Panama-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, the 1905 Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland, the 1907 Jamestown Exposition, the 1909 Alaska Yukon Pacific Exposition in Seattle, and others. A few of these furnished the opportunity for the issuing of commemorative coins, but most did not. In a typical situation of unfulfilled numismatic hopes, great expectations were raised for the 1907 Jamestown Exposition, held to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the establishment of the first white settlement in Virginia, and Farran Zerbe led the way for a commemorative $2 coin of which millions were to be sold. However, the idea died aborning.

The 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition was planned to outdo all of the other fairs that had been staged earlier. Foreign countries, domestic manufacturers, artists, concessionaires, and others were invited to become part of what eventually constituted a miniature city, whose sculptures and impressive architecture were intended to remind one of Rome or some other distant and romantic place, but which at night was more apt to resemble Coney Island. The object was to attract attention, draw visitors, make money, and enhance the glory of San Francisco.

The buildings of the Exposition were arranged in three areas. Festival Hall and several large exhibition "palaces" furnished the center of activity, flanked to the west by buildings containing the exhibits of 44 states, several U.S. territories, and 36 foreign nations, a racetrack, and a livestock building, and to the east by the amusement midway and seemingly innumerable concessions.