Walter Breen's Encyclopedia of Early United States Cents

Walter Breen

1794

(918,521)

According to Archives documents analyzed by R. W. Julian, (Julian, "Cent Coinage of 1794-95," Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine, January 1975, p. 6-7.) planchets for the 1794 cents were made from three shipments of British plate copper (ultimately from the copper mines of Anglesey, Wales) and four purchases of domestic scrap. In November 1792, Thomas Pinckney had arranged with Taylor & Bailey, of London, for the shipments, however, delivery was greatly delayed (the arrival dates are shown below). This plate copper was furnished to specifications devised by David Rittenhouse and Henry Voigt. The intention was to bypass the Mint's primitive rolling mills so they could be saved for making gold and silver planchet strip. Standardizing strip thickness averted more than half the difficulties facing any mintmaster of the period.

The figure Rittenhouse and Voigt specified for thickness has not been published. If they were thinking in terms of Birch cents at 20/16 (31.8 millimeters) diameter and 264 grains (17.110 grams), the thickness would have been 2.4 millimeters. The 1794 thickness had to be such that the finished coins would weigh the statutory 208 grains (13.478 grams) each. At an 18/16 diameter, this would be 2.35 millimeters.

In practice, diameter, thickness, and weight vary greatly. Chapman (The United States Cents of the Year 1794, Philadelphia, 1926, p. 9.) gave a range of 192 to 222 grains (12.4 14.4 grams): a deviation of over (plus or minus) 6% of legal weight. Silver coins 6% light would have been condemned by the Assay Commission as debased-risking prison terms or death for guilty officials. However, quality control on copper was evidently much less stringent. The observed weight range suggests that sheets were cut into strip and punched into blanks without regard for proper thickness.

Buying copper in plates or sheets (rather than pigs, lumps, scraps or ingots) was the next best thing to the then-impossible dream of buying ready-made planchets of uniform weight. (Boulton & Watt were to make the dream come true in a couple of years, and from then until 1857 the Mint preferred importing its copper blanks to making them.) Planchets made from scrap, including many of the Heads of 1793, were necessarily inhomogeneous and apt to develop slivers, laminations, cracks, or pitting. Though in collectors' eyes these add to the individuality of the coins, in Rittenhouse's day such defects were an adverse reflection on the Mint's quality control and might even have raised official doubts about the institution's competence. The Birmingham token coppers then circulating in quantity G. Hancock's Starry Pyramid halfpence, from Obadiah Westwood's mint, and Thomas Wyon's Talbot Allum & Lee cents, from Peter Kempson & Co.) were well designed and well struck on good copper, mostly free of such defects; their only flaw was light weight (most were struck at 40,46 or even 50 to the pound, compared to the Mint's cents at 33-17/26 to the pound). (Breen's Complete Encyclopedia, pp. 102-3,128-9.) It would not be satisfactory to circulate federal coins that looked worse than lightweight Birmingham coppers. That would give additional ammunition to the Mint's enemies, who expected to profit by abolishing the institution and negotiating with Birmingham token makers. These parties were already agitating for a Congressional investigation, which proved to occupy much of 1794-1795. According to Julian, (Julian, "The Mint Investigation of 1795," Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine, July 1961, p. 1713.) early Philadelphia Mint history "consists principally of attempts to abolish it." (More details about the Boudinot Committee's investigation will be found below, under 1795.)

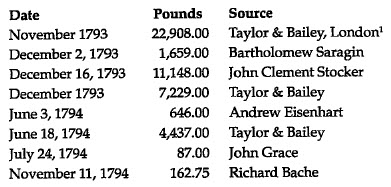

The Mint's copper purchases for 1794 cents were as follows: (These figures are mostly from Julian, "The Copper Coinage of 1794," Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine, March 1963, p. 949-951 and "Cent Coinage of 1794-1795," Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine, January 1975, p. 14.)

Stewart (Frank H. Stewart, History of the First United States Mint, p. 74.) says the first of the two 1793 Taylor & Bailey shipments was bought August 10, shipped on board the Pigon (under Captain Loxley), and weighed 21,408 pounds: the second, bought September 26 and shipped on board the Mohawk (under Captain Allen), weighed 8,229 pounds. The Saragin copper was probably used for making 10,000 half cents (delivered February 22, 1794), and probably for some (perhaps all) of the half cents delivered in March and June 1794; the Eisenhart copper would have sufficed for the rest.

Many, if not all of the earliest of the Heads of 1793 (numbers 1a, 2a) were made from the last leftover planchets from the Ferdinand Gourdon copper purchase (August 1793); they have the same finish, the same streaky toning, and the same kind of planchet defects as the final 1793 Caps, differing greatly from the texture of later varieties.

On the other hand, numbers 2b, 3b, and 5-8 are usually on finer blanks with fewer defects. Most likely these were made from part of the first Taylor & Bailey shipment.

It may not be coincidental that the edge device of 1793 was abandoned early in January. Voigt may have asked Scot to turn the leaf over, specifically to distinguish the new blanks from the old, just in case the earlier planchets' poor quality were to occasion any official inquiries. The low grade of survivors of numbers 1b, 3a, 4a, and 4b leaves this question unanswered.

The three Taylor & Bailey shipments must have yielded at least 346,000 blanks, probably over 500,000; the Stocker purchase, over 112,000 more, probably at least 200,000. Julian said that the Mint ran out of cent blanks in June 1794, resuming delivery after the third Taylor & Bailey shipment was cut into planchets.

The following tabulation of deliveries underlies all later discussions and reconstruction of 1794 cent variety mintages," Assignment of varieties derives from conclusions reached independently below: uncertainties come from a few extreme rarities (Sheldon's NCs), all of which share at least one die with less rare varieties, and must have immediately preceded, followed, or interrupted them.