Walter Breen's Encyclopedia of Early United States Cents

Walter Breen

1798

(Mint report, 979,700)

At the beginning of the year, the coiner's department had on hand nearly 319,000 blanks from the poor quality Coltman shipment of October 1797. Some of these may have been coined but not yet recorded as delivered. The Mint also had accumulated several tons of clippings, spoiled cents, and other scrap copper, (Largely from the Coltman copper of early 1797.) but Mint Director Boudinot was averse to making cents out of them, and had begun selling them off to local coppersmiths, keeping some for alloying gold and silver. The "sows ear-to-silk-purse" operations necessary to make clippings into planchets required melting, rolling into strip, cutting from strip, cleaning, and upsetting to impart raised rims. Not only would these processes entail additional labor costs and take time better used for other tasks; worse, the Mint's primitive rolling mills (always prone to malfunction) had to be saved primarily for gold and silver. The large coinage orders for half eagles, silver dollars, and dimes had higher priority than copper cents.

Coinage continued from the Coltman blanks through part of July, comprising the last dozen or so varieties dated 1797 and at least the first nine or 10 dated 1798. Survivors are often porous and discolored. Their texture differs markedly from that of later varieties.

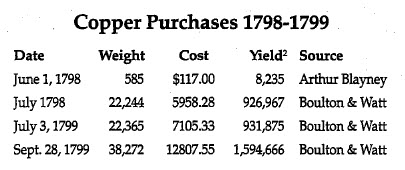

On June 1, 1798, Boudinot bought over a quarter ton of sheet copper from Arthur Blayney, but this stopgap lot did not go into use until mid March 1799, yielding 12,167 blanks for half cents (R stock) and 8,235 for cents.

Early in July 1798, a shipment of almost 10 long tons arrived from Matthew Boulton aboard the Amelia, costing 64.3 cents per hundred blanks (compared to 64.5 cents for the 1797 Boulton shipment). Explaining the lateness, Boulton complained of delays in receiving copper from the Anglesey (Wales) mines: inland canals had unexpectedly remained frozen long after the normal spring thaws. These blanks were used for cents through March 1799.

Two more shipments from Boulton followed in the summer of 1799; one arrived around July 3, the other around September 28, respectively costing 76 cents per hundred blanks and 80.3 cents per hundred: a source of worry to Boudinot, as the less profit the Mint could make on cents, the more ammunition available to congressional opponents seeking to abolish the Mint. About 185,000 of the July 1799 shipment arrived so blackened as to require cleaning; others, less discolored, went to press as is. The September 1799 shipment arrived while the Mint was closed for the annual yellow fever epidemic. These were used through 1800, and evidently many of these too, were discolored by the time they reached the Mint. In the meantime, Coltman had asked Boudinot to place a third order for planchets; the Director agreed only on condition that Coltman match both Boulton's quality and Boulton's price. There was no reply.

We deal with these later planchet shipments in this chapter because most of the cents coined during 1799 (and some in 1800) were dated 1798. Die state evidence proves that all the 1799 overdates preceded many of the commonest varieties of 1798. (The 1799 Perfect Date coins were probably made in 1800, as they are on the same black planchets as many varieties dated 1800.) Part of the reason for the mixing of dates and reverse types: the engraver was running short of die steel of the proper 1.5 inch diameter, and Boudinot had been trying to import more from England through both Samuel Bayard and Matthew Boulton.

(2 Theoretical, after Julian; excludes spoiled cents.)

Following the lines of reasoning set out under 1796 and 1797, these different planchet shipments should be distinguishable by texture and edges; and in fact the edges of 1798 cents are as diverse as those of 1797. Numbering is continuous with the latter, reflecting their overlap with the 1797 planchets.

IV. PE, Plain Edge. Found on all varieties with the possible exception of number 14. Several variants are not always distinguishable on worn coins. Some have convex (beveled) edges while others are normal and apparently unmarked. Some have traces of beading, less obvious than on edge II or VI. Another has a long diagonal bar, as on some 1797s. Still others are very irregular, showing areas of smooth cylindrical surface with faint transverse scrapes or polish marks from the blank-cutter. Coltman blanks are as on later 1797-dated coins. Boulton blanks may be from the July 1799 shipment.

V. RE, Reeded Edge. Faint diagonal and vertical reeding, the same as in 1797. This has a raised area similar to the elongated beads of the next but is not identical (Denis Loring calls both versions "welder's beads"). Found on numbers 1-10, 14, 15, 20, 24, 28 and many later varieties. Coltman blanks and others including cut-down British tokens (see number 24). (Both McGirk (1913) and Oapp (1931) described this edge.)

VI. SBE, Second Beaded Edge. Few elongated pellets or beads, similar to edge II of 1797, butnotidentica1. No diagonal reeding is present Found on scattered later varieties of 1798 including numbers 11, 15, 21-22, 32-33, 43 and possibly others. These may have been the Blayney shipment.

VII. DFE, Double Flange Edge. Thin incuse line or groove at both the upper and lower parts of the convex cylindrical surface of the edge. Found on many later varieties of 1798 including numbers 9, 11, 13, 15, 17-23, 27, 29, and 30. These Boulton blanks possibly come from the July 1798 shipment. Some of these were "black" (discolored by salt spray and bilgewater enroute).

VIII. SFE, Single Flange Edge. Thin incuse line or groove at either the upper or lower part of the convex cylindrical surface of the edge but not both at once. Found on some later varieties of 1798 including 36, 39, 40 (and possibly others), and early varieties of 1800. Boulton blanks perhaps from the July 3, 1799 shipment.

As Julian (British Planchets and Yellow Fever," Numismatic Scrapbook, June 1975, p. 41. Wumismatic Scrapbook, June 1975.) conjectured, much mixing of Boulton and Coltman blanks took place in and after July 1798. The evidence of edges, while incomplete, is ample to confirm this. The mixing was too extensive to be accidental. This circumstance increases the difficulties in constructing an emission sequence.

As in 1793 through 1795, and 1797, different edges should logically constitute subvarieties, but they are not always distinguishable on worn, corroded, or heavily patinated specimens. In each variety description at Edge, I list all edge variations observed since the present study began, but this information is too recent for even a reasonable attempt at completeness, let alone rarity estimates. Perhaps in subsequent references others will £ill these gaps.

The following tabulation, like the preceding historical sketch, summarizes much in Julian (Numismatic Scrapbook, June 1975.) though the version of the former printed in Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine omitted tabular delivery figures for 1798.