Walter Breen's Encyclopedia of Early United States Cents

Walter Breen

In 1800 the obverse device punch was chipped on the right side of the lowest curl, producing a short straight vertical contour. This does not show clearly on dies of 1801 or later years. Either each die was hand retouched to eliminate it, or a new device punch was raised from the 1799 matrix.

The earliest reverses for 1801 cents were "Type of 1799" dies left over from 1800: Sheldon's "minor variants from reverse A." One of these (reverse B) was the severely clashed die of 1800 number 29; the others, reverses A, F, and G, are quite similar. After Scot had completed 1801 reverse A, the N punch chipped, first at one serif of the right upright, later at the right foot of the left upright. The N punch chipped on the upper serif appears only on N(E) in reverses B of number 3 and F of number 9; on N(E) and N(T) in reverse G of number 10; with intact feet on all three NS in reverse C of number 5; and with broken feet on all three NS on all later 1801 dies. The last 1801 reverse made is likely to have been H of number 12, with all four TS broken and their right feet hand restored. This T punch recurs in half eagles and quarter dollars as late as 1807, even after Scot had obtained new letter punches for cents. One "Type of 1799" die was left over for 1802 use, but the hub was evidently abandoned.

Later 1801 reverses, like those of 1802-07, were made from wreath punches with letters entered by hand; positional variations became very marked, and Scot's carelessness (or deteriorating eyesight) resulted in spectacular blunders. Four reverses show the error 1/000: E, G, J, and K (of numbers 8, 11, 12, 15, 17). A fifth, C (of number 5) was hastily corrected, "1/100 over 1/000." Reverse E also lacks the left stem end and has u first entered inverted (rotated 1800) then corrected: the famous "Three Errors," known a century ago as HNITED or IINITED. Reverse L was used earlier in 1802; reverse K was annealed and corrected for 1803 service. Only two of the five varieties are rare, and number 17 is plentiful. The need for dies must have been acute to allow such blunders to be issued in quantity. The explanation is manifestly as in 1800: die steel was in short supply, and existing dies had to be used as long as they would last, including rejects. Extensive and even bizarre die breaks, notable in 1800, occur also on cents of 1801, notably on numbers 3, 4, 5, 9-13,16, and 17. There are no details about the next arrival of die steel from England, but the same problem recurred for the next few years. (R. W. Julian, "Die Steel Shortage Plagues Coiner," Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine 10/1973, p. 893.)

Sheldon suggested another possible reason for these blundered dies:

In March 1800, a committee of the U.S. Senate recommended abolishing the Mint on the ground that the expense of coinage was altogether disproportionate to the advantages derived from [the very limited] circulation of its coins. This committee branded the Mint experiment a failure, and suggested that another arrangement should be made [with some private concern] for providing the nation with coins.

A second bill for abolishing the Mint was introduced in Congress in April, 1802, and only after most vigorous debate was pigeonholed nearly a year later. During these years all employees at the Mint were reminded frequently that the tenure of their jobs was uncertain, that reductions in pay were probable, and that to keep a weather eye open for a safer job would be a good idea. In the light of this general state of affairs, such cents as the 'three errors' variety of 1801, the recurrent denominational fraction 1/000, the "LIHERTY" cent of 1796, misstruck, overstruck, understruck, and badly centered coins, the use of defective planchets and of shattered dies, the occurrence of freak coins and of oddly individualistic experiments like the so-called Jefferson cent of 1795-all these symptoms of uncertainty and poor discipline take on sympathetic significance. Those fellows had been doing their best with a tough assignment and were getting about the encouragement of a soldier in peacetime. Something was being "expressed" in the early cents. (Early American Cents, p. 13 and Penny Whimsy, p. 13.)

Later Sheldon added:

We know that morale must have been low at the Mint during these years, and it is not so very surprising to find a number of peculiar or bizarre errors on the coins; especially on those of 1801, which was possibly the darkest year at the Mint. It is these very errors and peculiarities that endear the old cents to those who know them well. (Early American Cents, p. 258 and Penny Whimsy, p. 270.)

In light of what we now know about Mint conditions, Sheldon's conjecture seems at once oversimplified and unduly metaphysical, and the actual explanations are very different. For the "Jefferson" cents, see above, under 1795; for the defective planchets, see the discussions of Coltman blanks above, under 1796 .. 98; for the shattered dies, recall previous paragraphs.

Julian (R.W. Julian, ''The Cent Coinage of 1802," Coin World, April 6, 1977, p.28.) gives a third conjecture: that "the sudden press of coinage after so long a dry spell without planchets may have been a strong factor," requiring Scot to work in unusual haste, and suggesting that he may have used otherwise idle coiner's department laborers to complete the dies. Scot's putative use of laborers, however, is less likely than it sounds. On the one hand, doing layouts for each die and training workmen to enter letters and numerals would have taken more time than finishing the task himself; on the other, die steel was in such short supply that Scot would hardly have risked working dies by trusting them to untrained workmen.

In summary: The die steel shortage, and haste in furnishing dies to complete large coinage orders, suffice to account for an issue of cents with bizarre breaks and blunders. Possibly no further explanation is needed.

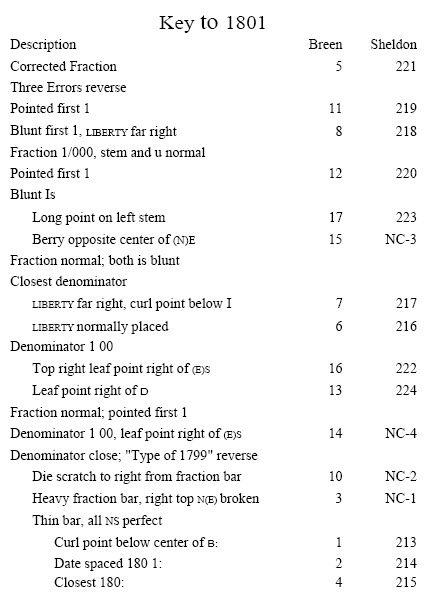

The actual emission sequence is less neat than the simplified versions in Newcomb and Sheldon. However, die states have provided convincing evidence within the die linked groups 1-4, 5-12, and 14-17. The group 1-4 belongs first because of the pointed first 1 and the ''Type of 1799" reverses; the group 14-17 comes last because two of its reverse dies were reused in 1802-3; and the group 5-12 falls naturally between them. The only remaining uncertainty: did our number 13 follow 4 or 12? There is not enough evidence to decide.