Walter Breen's Encyclopedia of Early United States Cents

Walter Breen

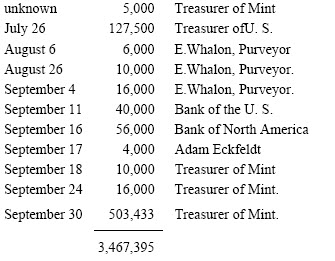

The discrepant amounts in the first half year may represent coins struck in 1799 but delivered later.

"E. Whalon" or ''E. Whalen" (above and in delivery tabulations for 1801-2) refers to Israel Whalon, the Philadelphia deputy of Thomas Tucker, Treasurer of the United States. By law, Tucker was responsible for distributing copper coins. After the federal capitol moved from Philadelphia to Washington in 1800, Tucker distributed them through Whalon. Many of the cents went directly to local banks; others to Custom Houses (along the Atlantic coast or the Canadian border) and small businesses. In late 1803, Tucker replaced Whalon with Tench Coxe.

Beyond doubt 1800 is the most difficult date of the first decade to find in choice condition (other than 1799), and it is far and away the most difficult date to attribute: a combination leading to its generations-old repute as the most frustrating of all. One byproduct was neglect; another is cherrypicking.

Many collectors, including Sheldon, have long suspected that cents of this date are of a typically soft metal, softer than other early dates. (Early American Cents, p. 238; Penny Whimsy, p. 248.) Using a Tukon Micro-Hardness Tester, Ray Williamson examined this hypothesis on worn cents of various dates. The 1800 in his sample (our number 23) was only 59% as hard as an 1826 Newcomb 8.2 The source of this variation remains uncertain. There was no documented change in striking method; nor were the surfaces of Boulton's planchets routinely chemically altered before striking. Was the copper ore of one of the Boulton 1799-1800 shipments softened by trace elements? Were these the blanks damaged by salt spray and/or bilgewater enroute from England, requiring scouring or acid cleaning? Little can be deduced from this one test, however, testing hardness on a large sample of individually weighed 1800s, with edge devices recorded, including all the less rare varieties, might enable us to distinguish the various planchet sources.

Die layouts remained unchanged from those of late 1798 and 1799. The first obverse described is a Head of '99 overdate, die linked to a Head of '97 die dated 1798 and altered to make 1800/1798; there is no proof that these were the first to go to press. All later obverses are from the Head of 1799 hub; the lowest curl is chipped at the part nearest 1 in date (vague on some dies, and corrected by hand on obverses of 20 and 29). Five of these obverses are overdates, 1800/179-. All of these are from previously unused dies, completed in late 1798 for 1798 or 1799 use but with the final digit effaced or omitted. All have the small 7 found on the last two obverses dated 1798. In later dies without the overdate, the 1 is normally closer to the curl than on other dates from 1796-1807; evidently Scot felt he needed to leave plenty of room for the broader digits 00.

All reverses are from the "Type of 1799" hub, by now showing wear and tear. (Possibly from another hub made from the same matrix. The extensive hand strengthening on all working dies makes this indeterminable.) T(ED) and (M)ER often show more irregularities at their tops than in the similar 1798-99 "Type of 1799" dies (perhaps from injuries to the hub). The upper left serif of the numerator is normally shorter than that in the denominator and the fraction bars are normally more variable than in the 1798-99 dies and usually much longer. Sheldon nevertheless so far forgot himself as to say "there is really only one 1800 reverse." (Early American Cents, p. 238; Penny Whimsy, p. 248.)

The emission sequence is largely guesswork. I follow Clapp in placing the overdates first. Their SFE blanks link them in time with the late varieties dated 1798. The probable time was January to February 1800. The group following the overdates contains several reverses evidently left over from 1798: they have the defective C(E) punch with broken serif. Some of these also come on SFE blanks. Except for number 12 (which immediately followed the overdate 11 with the same reverse, though possibly made long after other overdates), the obverses with broken or noticeably repaired Yare placed late. Note that the final obverse (variety 29) has a broken Y and a reverse reused in 1801.

Ross numbers are from George R. Ross, "U. S. Cents of 1800," a paper presented to the 1930 ANA Convention. (Numismatist April 1931, pp. 254-7; Lapp & Silberman, pp. 379-82.)

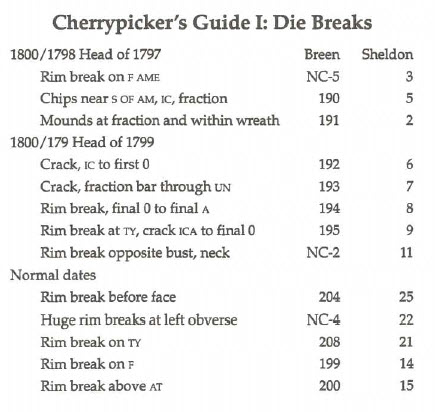

This date is notable for bizarre and extreme die breaks. The explanation (from R. W. Julian) is that the engraver's department was short of die steel, and accordingly used dies until long after they would normally have been discarded. Some of the breaks are distinctive enough to provide instant identification.