Walter Breen's Encyclopedia of United States and Colonial Proof Coins 1722-1989

Walter Breen

Nor are domestic state coins or patterns for the Confederation found in prooflike state. The technique may not have been known to anyone in the local mints.

On the other hand, some dated in the 1790's definitely do pose a problem. (a) The 1791 Large Eagle cents sometimes come with beautiful prooflike surfaces. I have seen several gilt, but do not know if this was done before or after striking. I have heard of a specimen coming in brilliant proof in original case of issue, but not seen it. (b) A single brilliant proof Small Eagle cent of 1791, in original presentation case, appeared at an auction in 1865. Where it is now I do not know. (c) The 1792 "Roman Head" Washington cent is usually said to come in proof. (d) Proofs in copper and silver supposedly exist of 1794 and 1795 Talbot, Allum & Lee tokens, as well as of the mules using the 1794-95 LIBERTY & COMMERCE stock reverses found on those tokens. (e) The dateless (1795?) Washington penny token with LIBERTY & SECURITY comes prooflike and occasionally gilt. (f) The dateless (1792-95?) "Kentucky," "Triangle" or "Pyramid" token, showing 15 stars each stamped with the initial of a state, K for Kentucky at top, usually comes more or less prooflike; specimens are often sold as proofs. (g) The 1795 Washington Grate halfpenny (usually miscalled a "cent") often comes prooflike, and specimens likewise reach buyers labeled as proofs. (h) Castorland half dollars - originals and early restrikes -come in proof state. (i) The very rare undated (1795-97?) THEATRE AT NEW YORK Penny, though listed in earlier editions of the Standard Catalogue only in Fine and VF, is known prooflike and apparently in no other condition. I shall deal with these nine problems in order preparatory to continuing and finishing the list of Colonial proofs.

(a) The 1791 large and Small Eagle cents are known to originate with the elder John Gregory Hancock, Birmingham medallist. (Cf. Eckfeldt & DuBois, Pledges of History, 1846; Crosby, Early Corns of America, 1875, mentions an unfinished-die trial piece coming from Hancock's widow.) This man did create tokens and medals of the regular prooflike kind, and a few of far superior order which would have to be called brilliant proofs - in higher relief. Comparison removes doubt: the Large Eagle cents are of the former sort. Between the finest prooflike ones yet seen, and those from later die states with definite mint bloom and somewhat rougher finish, there is no clearly marked distinction. Further, both the former and the latter have rather weak borders on both sides, and somewhat indistinct striking up on Washington's hair and coat. This is true also of all the gilt specimens I have seen. If any true proofs were made, therefore, they would almost have to be confined to the unseen presentation-case specimens known only to rumor. (I have vague recollection that one of these might have been in one of the A.B. Sage sales ca. 1859-60). Most probably they would be on unusually wide flans, with unusually full serrated borders and needle-sharp definition on Washington's hair and coat, having been made by processes like those in use at the Royal Mint for proofs.

(b) The same comments made for the Large Eagle cents, above, hold true for the Small Eagle, except that uncirculated specimens of this issue are very rare, prooflikes almost unknown, gilt specimens unseen. In the Bache sale, held by W. Elliot Woodward in. March 1865,' lot 3273 was a Small Eagle cent described as brilliant proof in original presentation case of issue. I have no idea where this piece might be.

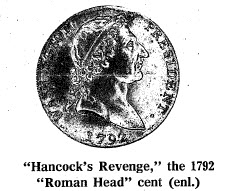

(c) However, the 1792 "Roman Head" Washington cent is another matter, altogether different. This is a satirical piece - "Hancock's Revenge" - privately distributed by John Gregory Hancock on behalf of Obadiah Westwood, lampooning Washington's objections to portrait coinage as "monarchical", in revenge for G.W.'s having killed contract coinageproposals. Supposedly 12 are known. I have examined seven different ones, all in copper with the same edge, together with the Merkin-Picker uniface trial with I.G. HANCOCK F. instsead of date, and Dr. George Fuld's unique white metal trial piece from a rejected obv. with beaded borders and spelling error PRESEDENT. (It was earlier in New Netherlands' 39th Sale, before that in a Glendining sale in the 1930's.) The copper specimens are in high relief, well centered and struck with full borders and brilliant mirrorlike fields; they show all earmarks of intentional brilliant proofs. The old story that the 12 known of these came from a packet of British tokens consigned to Jeremiah Colburn (fl. 1858-63) makes sense in this context, too; very likely these 12 (plus perhaps a few held out by the maker) were the only ones ever coined.

(d) The Talbot, Allum & Lee tokens of 1794-95 come in many die varieties, and (except for the piece lacking words NEW YORK) often in olive to bright red mint state with moderately prooflike surfaces, the 1795 far more often so than the 1794. Specimens are also found to the present day in batches of unattributed 18th century tokens imported from England. I have seen them from varying states of broken or worn dies, ranging from moderately prooflike to frankly frosty uncirculated with no clear demarcation between the two classes aside from a very few 1795 perfect-die proofs, e.g. Morton: 604 (Pine Tree, Oct. 1975). The same remark holds for the various mules, except for the York Cathedral piece which I have never had an opportunity to examine, and the very rare BLOFIELD CAVALRY mule which I have seen only twice. Further, some of the mules are almost always weakly and unevenly struck from worn dies. The conclusion is clear enough: with very rare exceptions none of them qualify as proofs; they are instead quite typical of the later token-craze pieces, thin and poorly struck from any irrelevant dies on planchets with any edge, merely to satisfy collector cravings for something nobody else has got. Even the silver specimens are of fabric far inferior to authentic proofs of the period.

(e) The dateless (1795) Washington penny token with LIBERTY & SECURITY often comes prooflike and occasionally gilt. I have never seen a prooflike one with the so-called "corded rim" -diagonal ornaments outside the linear circles of border -nor have I seen a prooflike specimen well enough struck on Washington's hair or coat to qualify as proof, though rumors -of such recur. Identity of design, punches and fabric between this and the very rare dated 1795 penny and the similar halfpenny forces ascription of all these to the same makers, namely Kempson & Sons. Since the halfpennies are usually on small thin flans some of which read (like the pennies) AN ASYLUM FOR THE OPPRESS'D OF ALL NATIONS, we can attribute the planchets to William Lutwyche, one of the more careless and venal of the Birmingham Hard Ware Manufacturers; R. H. Williamson has pointed out the frequency of this edge on many of Lutwyche's tokens

(f) The dateless (1792-95?) token commonly called the "Kentucky Cent," "Triangle" or "Pyramid" token, and known to originate in Lancaster, England, presents one of the more difficult problems. The piece is attributed to Kentucky with no good reason; its legends prove it to refer to the Colonies in general. Its triangular array of 15 stars has each star stamped with the initial of a state, the topmost being K for Kentucky, the 15th state (1792), the next two being RI. and Vt. for Rhode Island and Vermont (1791), the 13th and 14th states to enter the Union. From the arrangement, one could make a very plausible guess that the token's designer was referring to the Masonic "Unfinished Pyramid" device on the $50 Continental notes of 1778-9, in the belief that the admission of Kentucky as 15th state completed the roster. (Were the roster then thought incomplete, nothing would have been simpler than to arrange the 15 stars in three rows of 6, 5 and 4, making a still unfinished pyramid.) Most lettered edge specimens of this token come with some prooflike surface; the plain edge pieces normally come Fine to AU. The prooflike ones occur in lots of unattributed British "Conders." They come on wide and narrow flans with plain edge, and on somewhat wider ones with various edge letterings and - extremely rarely - with diagonal reeding, the so-called "engrailed" edge. Once again, there seems no sharp demarcation between the most prooflike and the least prooflike ones; they come in earlier and later states of die breaks (the breaks are on the side showing hand and scroll), and even on the ones with diagonal edge reeding (which have the widest flans of all), borders tend to be weak, central area of scroll poorly brought up. I conclude that none of these were intentional brilliant proofs.