The History of United States Coinage As Illustrated by the Garrett Collection

Q.David Bowers

Many 19th- and 20th- century medals of the approximate diameter of a silver dollar have been designated as so-called dollars by collectors. A reference work, So Called Dollars, by Harold E. Hibler and Charles V. Kappen, chronicles over 1,000 issues. The 1826 completion of the Erie Canal, the 1909 Alaska- Yukon Pacific Exposition and the Hudson-Fulton celebration of the same year, the completion of the Panama Canal in 1914, the William Jennings Bryan presidential campaigns of 1896 and 1900, and the feelings and beliefs of private individuals ranging from Thomas Elder, the well-known coin dealer, to Aaron White (a Connecticut lawyer who distrusted paper money and who in the 19th century produced a token with the inscription NEVER KEEP A PAPER DOLLAR IN YOUR POCKET TILL TOMORROW),were among the many issuers and events in the so-called dollar series.

Particularly significant among so-called dollars are the 1900-1901 Lesher referendum dollars made in Victor, Colorado. Lesher, who believed in the future of silver despite its depressed price, issued a series of octagonal medals at the face value of $1.25 each, promising to redeem them at any time. To assure redemption an equivalent amount of money was deposited at a local bank. The idea spread, and Lesher pieces were soon distributed by a wide variety of local businesses, including A. B. Bumstead, a Victor grocer; J. M. Slusher, a grocer in nearby Cripple Creek; Sam Cohen, a Victor jeweler, and others. Adna Wilde, who studied the series in detail and published his findings in a 1978 issue of The Numismatist, estimated that fewer than 1,900 Lesher dollars were made totally. Of this number he was able to trace the precise location of 384 individual pieces which appeared in exhibitions, auction sales, and dealers catalogues over the years, a task made easier by the fact that nearly all Lesher dollars were stamped with a distinctive serial number.

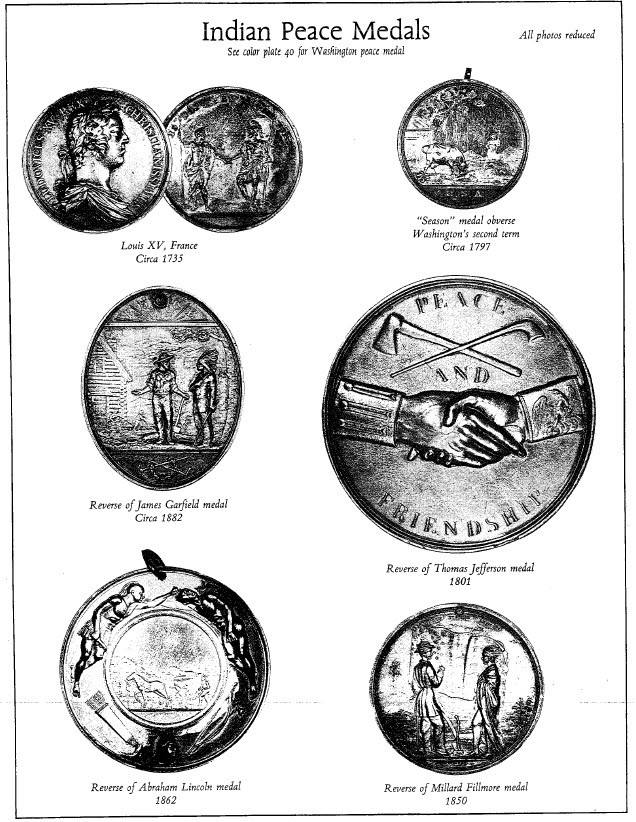

Indian Peace Medals

The discovery of America forced both a new world and a new people into the mainstream of European thought and politics. England, France and Spain each cultivated the loyalty and friendship of the Indian tribes surrounding their colonies. Good relations obviously added to the security of the fragile settlements, and loyal tribes were valuable allies when the interminable European wars spread to the colonies.

Silver medals,bearing the royal image, were awarded to the Indian chiefs and important warriors as an integral part of the European Indian policy. Trade goods and even firearms had practical advantages as gifts and rewards, but only the medals conveyed the esteem and prestige of favor with the European fathers across the water. The medals, worn proudly around the neck, fostered the same sense of honor, rank and loyalty to the Crown that European orders and decorations symbolized to the European aristocracy.

The Jesuits, on the leading edge of European intrusion into the wilderness, gave the Indians religious medals and symbols in their crusade to convert and civilize the savages. The peace medal was another replacement for their totems, and was undoubtedly believed by them to have the power of a talisman.

Two centuries later, it is difficult to fully appreciate the fragility of this new nation under the administration of George Washington. Most of the Indians had sided with the British during the Revolution, or better stated, had sided against colonial expansion. With the founding of an independent American nation, established on a continent largely populated and controlled by Indians hostile to the colonists, with loyalties established by custom to the now ousted foreign government, the new government faced the challenge of establishing an equitable yet effective Indian policy. This new policy, which provided for the establishment of peaceful relations while allowing for expansion beyond the artificially imposed boundaries of colonial rule, brought changes in the symbolism and purpose of the Indian peace medals. The Indians were realists and soon recognized that they must deal with a new Great White Father on this side of the Atlantic. At one of the earliest peace conferences, with the Choctaw in 1786, the American commissioners reported to Congress that the Indians wished to exchange their British medals and commissions for new American ones. As the government negotiated new treaties, terms often called for the conferring of great medal chiefs with appropriate ceremony and gifts. This young nation, conceived as a magnificent experiment in the tolerable limits of diversity, would be forced to test this concept with regard to these native inhabitants. As the attitude of the citizenry changed over the next hundred years, changes in government policy were dictated. The medals reflected these changes and the process and development of the culture which produced them. Today these medals provide a permanent and tangible history of our nation's expansion across a continent, as civilization was brought to the wilderness.