Walter Breen's Encyclopedia of Early United States Cents

Walter Breen

John Reich's Classic Head Design

1808-1814

For over a century the Reich design suffered from the misnomer "Turban Head." Edcuard Frossard, who surely should have known better, popularized this name in his 1879 monograph, and Sheldon perpetuated it with the rationalization "There is no turban, but the band, together with the way the hair is arranged above it, gives the superficial effect of a turban." (Early American Cents, p. 305; Penny Whimsy, P: 321.)

Ebenezer Locke Mason, Jr., proposed the term "Classic Head" in 1868. (Mason's Coin and Stamp Collector's Magazine, February 1868, vol. 1, no. 11, p. 99.) In the 1950s I revived the name, and it has caught on, but has not completely displaced Frossard's misnomer. What Mason perceived was evidently the resemblance between this design and any number of Greek statues----not of goddesses, however, but of boy athletes. A likely ancestor of the Reich design was some 18th-century engraving of the head of Polykleitos's (5th century BC) Diadoumenos ("Athlete Tying the Fillet"), which shows the fillet similarly placed. The profile is no more feminine on the Reich design than on its ancient Athenian ancestor: a circumstance which may have contributed to the Mint's shabby treatment of Reich (1768-1833).

The fillet (inscribed LIBERTY on the Reich design) was not worn by women; it was a prize for winners of citywide athletic competitions, ancestral to the blue ribbons awarded in dog shows and coin exhibits. This circumstance probably led to criticism of the design by classicists, and may have led to newspaper attacks. "It has been theorized that the reasons for Reich's leaving the Mint on March 31, 1817, after 10 years of service, included his not having had a raise in that entire time and the continued jealousy on the part of the superannuated mint engraver, Robert Scot, who was by that time 77 years old. For reasons that were never made public, Scot replaced Reich's Classic Head design on the cents, late in 1816, with his own 'Matron Head' design. Possibly, Scot's excuse was that someone had re-marked on the eccentricity of Reich's using the head of a boy athlete to represent Ms. Liberty. In any event, Scot died before he could redesign the half cent, which is just as well, as his eyesight was manifestly not up to the task: his half eagle head of 1818 is an inferior copy of Reich's, and his 1821 quarter eagle head is still worse. When William Kneass succeeded Scot in 1824, he resurrected the old Reich design for the 1825-36 half cents, and gave it an apotheosis on the new No Motto designs for the gold coins in 1834. From Reich's studio in the art colony on the Other Side must have come many satisfied chuckles at this vindication. Reich's design was now part of national public relations, as it never would have been on copper." (Half Cent Encyclopedia, p.291.)

Not that personifications of Liberty had to be female, especially considering that women could then neither vote nor own property. Forty years earlier, American revolutionary newspapers had even represented Liberty as a frontiersman with musket, a Minuteman with sword, a Native American, an unharnessed horse, or a bird escaping its cage. Less than a century later. Augustus Saint-Gaudens said that his concept of Liberty was "a leaping boy. (Numismatist, 3/1913, p.131; Complete Encyclopedia, p. 519.)

For Reich, the Classic Head design represented an opportunity for innovation, intended to discourage counterfeiting. Here, unlike Scot's earlier obverse designs, but like all to follow through 1857, the word LIBERTY was punched into the matrix or original die from which obverse hubs were raised; no longer would the engraver need to layout and enter this word onto every working die sunk from the hub. Lettering would therefore not differ from one die to the next; deviation would be grounds for suspicion.

Reich's reverse was equally innovative. His matrix included the wreath (of the Christmas kind) enclosing ONE CENT and a dash. From this he raised a hub, to sink into all subsequent working dies. No longer would the fraction, leaf stems, berries, berry stems, and ONE CENT have to be added by hand. This saved probably more than half the time needed to make each working die; it also minimized the amount of visible variation (and the chances of blunders), with the same anticounterfeiting purpose as in the obverse.

In practice, working dies received varying amounts of hand retouching even on hubbed elements, including sometimes the top lock of hair or a curl near the ear, and occasional repunching on LIBERTY and ONE CENT. What counted more was that the time formerly needed for layout was saved for other tasks. The obvious next step was standardizing positions of stars and letters, preferably by complete hubs; however, this did not become feasible until the Mint obtained a steam press in 1836. The larger the hub, the more force needed at press to sink it into each working die. Boulton had been using such methods as early as 1797, but until the 1830s no foundry in the United States could make large enough steam presses for the purpose.

Possibly the most remarkable property of Reich's dies was their longevity. The average number of impressions per die was close to 300,000, some reverses notably exceeding that figure. All dies sooner or later show evidence of clashing (most show repeated clashing incidents); many show "flowlining" (radial evidence of wear, as when stars or letters are joined to borders); many (most often reverses) show "blunting" (wear) near the borders; some dies crumbled at the edges; but few show any dramatic breaks. Lack of obvious breakage may explain why these dies were used until they wore out, long after other dies would have been discarded. Most likely their metallic source (one batch of die steel from Matthew Boulton) contained trace elements which rendered them less brittle than earlier or later working dies. Much hitherto unknown die state evidence was assembled by Pete Smith, independently of my own observations and often going well beyond them. ("States marked Smith (1985A) are from Pete Smith, "United States Turban Cents, 1808-1814," Coinage of the Americas Conference, New York: American Numismatic Society, 1985, pp. 150-74; those marked Smith (1985B) are from his letter to me, May 2, 1985; Smith (1988) from a list he prepared at that time.")

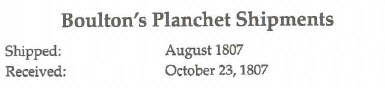

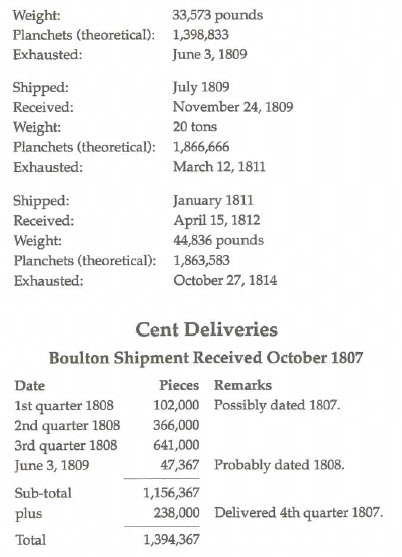

Planchets for the Reich cents were all from various Boulton shipments, however, some data remain incomplete. To make the following discussion intelligible, I append tables of planchet imports and coins struck, 1808-14. (The figures in the following tables are from R. W. Julian, "Mint Imports Copper Planchets in 1801/' Coin World, 3/27/1991, p. 32; "The Large Cents of 1809-11," Numismatist, November 1994; and ''The Cent Coinage of 1812-14," Numismatist, December 1994.)