“There is no great; there is no small; in the mind that cuaseth all.” ~Zitkala-Ša

Zitkala-Ša, also known by her anglicized name Gertrude Simmons Bonnin, was a Yankton Dakota Sioux Native American activist, writer, composer, and musician. She experienced a traumatic forced assimilation when she was young that led her to a career as a political activist. She used her musical and writing talents to share her Native culture and write scathing articles, criticizing the treatment of Native Americans.

Zitkala-Ša spent the first eight years of her life on the Yankton reservation, an experience that she often recalled as the safest, happiest, and freest period of her life. She learned the native language and was fully immersed in traditional culture. This all changed after she turned eight and the reservation was visited by religious missionaries looking to recruit Native children for a Western education.

Zitkala-Ša was taken to the Quaker boarding school, the Indian Manual Labor Institute. She loved learning to read, write, and play the violin, but despised the forced assimilation she experienced during her time there. She was forced to cut her long hair (an act that was against her cultural beliefs), was discouraged from using her native language, and was forced to pray like a Quaker instead of following her traditional beliefs. After three years, she returned home longing for a connection with her heritage. She was devastated to find that she no longer fully fit in with those on the reservation and was even more upset to find that many were starting to conform to the dominant white culture.

When Zitkala-Ša was 15, she decided she wanted to finish her education and returned to the Institute. She took a special interest in piano and violin, and started teaching these subjects when the music teacher left the school. After graduating, she attended Earlham College on a scholarship. While there, she focused on developing her writing and speaking skills, giving many activist speeches and translating traditional Native American stories into English to share with others. After college, she spent two years studying music at the New England Conservatory of Music.

After finishing her education, Zitkala-Ša took a job teaching music and facilitating debates at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. While there, the school's founder sent her back to the Yankton reservation to recruit new students. When she got to the reservation, she was saddened to learn that their land had started to be taken over by the Westerners. When she returned to the school, she began butting heads with the founder. She started writing articles that publicly criticized the American Indian boarding school system and its Indian deracination efforts. She shared her own story to demonstrate how harmful forced assimilation is to children. One of these critical articles, "The Soft-Hearted Sioux," got her fired.

After leaving the school, Zitkala-Ša returned home to the Yankton reservation to care for her mother. While there, she threw herself into her writing. She began to gather traditional stories for her book, Old Indian Legends. She worked hard to collect Native legends and stories from multiple tribes and translated them into English so they were accessible to those outside of the tribes. She also wrote the book American Indian Stories, which was a collection of childhood stories, allegorical fiction, and essays. It told the stories of hardship that she and others experienced during their forced assimilation at the missionary schools. Her writing was dynamic and liminal, highlighting the tension between tradition and assimilation. Zitkala-Ša also wrote many autobiographical narratives that countered the idea that Native Americans were excited about the opportunity to conform to the Western Christianity being forced on them.

In 1902, Zitkala-Ša moved to the Uintah-Ouray reservation in Utah. There she met William F. Hanson, a composer and professor at Brigham Young University. They collaborated on writing The Sun Dance Opera, the first ever Native opera. Zitkala-Ša wrote the songs and libretto while Hanson did the composition. The opera was based on the Lakota Sun Dance, which the government prohibited the tribe from performing. The Sun Dance Opera debuted in 1913 and received critical acclaim and high praise.

Zitkala-Ša had always been a politically active figure and was an active member of the Society of American Indians (SAI), an organization dedicated to preserving the Native way of life while advocating for full American citizenship. In 1916, she was appointed the National Secretary of the SAI and relocated to Washington, D.C. She started working closely with the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), but quickly came to criticize their practices. She was heavily opposed to the BIA's attempt at national boarding schools for Native children, where they would not be allowed to use their native language or engage in cultural practices.

While in D.C., Zitkala-Ša began to lecture nationally, speaking out against the harm of forced assimilation, often sharing her own experiences to make her argument more compelling. She helped pass the Indian Citizenship Act, giving citizenship to indigenous people, founded the National Council of American Indians to unify tribes against the discrimination they all faced, and was an activist for women's suffrage. In 1924, she published the article "Oklahoma's Poor Rich Indians," exposing American corporations using extreme measures, including murder, to defraud Native tribes when oil was discovered on their lands. This article influenced the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, which returned some land to certain tribes.

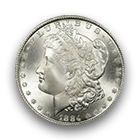

The design for the Zitkala-Ša quarter was discussed at the March 1, 2023, Citizens Coinage Advisory (CCAC) meeting. Her great-granddaughter, Holly Ogle, and great-great-grandson, Mark Bonnin, attended the meeting to share their thoughts on the design. They appreciated the specific references to her author, activist, and composer accomplishments. They felt that all three were essential components of her story and were happy to see all represented. The book Zitkala-Ša holds represents her work as an author and activist, and the stylized sun behind her represents her opera and work as a musician. The committee appreciated this engaging portrait because, as a political activist, Zitkala-Ša always had to engage with others. The eye contact from her portrait makes it look like she is staring right at you, drawing you in.

This quarter also includes multiple nods to Zitkala-Ša's Native American heritage. She is pictured in a traditional dress, with her hair in two long braids. In many Native cultures, long hair is connected to a strong cultural identity. During her time at the Institute, Zitkala-Ša was devastated when she was forced to cut her hair since it felt like she was cutting ties with her culture. So the long braids in this portrait are an important part of her story. The diamonds in the background are a traditional pattern, and the red cardinal flying above is a reference to the Lakota translation of her name, "Red Bird."

Copper & Nickel

Copper & Nickel

Silver Coins

Silver Coins

Gold Coins

Gold Coins

Commemoratives

Commemoratives

Others

Others

Bullion

Bullion

World

World

Coin Market

Coin Market

Auctions

Auctions

Coin Collecting

Coin Collecting

PCGS News

PCGS News