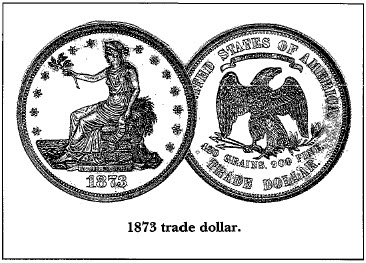

Silver Dollars & Trade Dollars of the United States - A Complete Encyclopedia

Q. David Bowers

Design Selection

On June 4th Linderman again visited Philadelphia and examined the Barber patterns, which had just been made. The director decided that the latest obverse was nearly perfect, but nevertheless ordered certain changes, notably on the base which was shortened. For the reverse eagle, Linderman directed that the one from Judd-1310 through 1314 be used but enlarged as shown on Barber's latest drawing. The decision had now been made although technically the Treasury had yet to approve it. Linderman took care of that problem very quickly.

On June 9th Barber wrote the director that the new plasters were nearly ready and the galvanos would shortly go on the Hill machine for reduction. According to the engraver it would take 26 days to prepare working dies for the coining presses at Philadelphia. It would be a further eight to 10 days before dies could be sent out to the mints at Carson City and San Francisco.

In early July, just as the working dies were being prepared, Linderman wrote Pollock, who was now superintendent of the Philadelphia Mint, that all haste must be made as the Mexican government had ordered the suspension of the balance scale pesos, which had not gone over well in international trade since their introduction in the 1860s, in favor of the old 8-reales design. There was no time to lose if a foothold was to be gained in the Oriental silver trade.

Coinage Commences

July 11th saw the first Philadelphia coinage with appropriate ceremonies. There was no delivery until the 14th of the month, when 40,000 pieces were taken by the coiner to the superintendent. (The 1873 coinage act had abolished the treasurer's post and given that responsibility to the superintendent.) From this point on coinage at the parent mint was rather heavy, with nearly 400,000 coined in 1873. Nearly a million were struck in 1874, but after that, mintage at Philadelphia declined significantly until reviving in 1877.

Carson City received four pairs of dies on July 22nd, after a trip of only 10 days by train, while San Francisco's six pairs arrived about the same time. Carson coinage began immediately as did that at San Francisco, but by year's end the California mint had far outstripped its Nevada cousin, 703,000 to 124,500. Coinage at both mints was relatively heavy through 1877, while San Francisco produced the bulk of the struck coinage in 1878.

Sales to Collectors

Collectors wanting examples of the first trade dollar had problems because, by law, regular coins could be paid only to the person depositing the silver bullion. Unless the collector was personally acquainted with such a person, there was no way to get the ordinary trade dollar. On the other hand, the Philadelphia Mint did sell Proof coins at reasonable rates and a number of collectors took advantage of this service.

It was normal practice in the 1870s for the numismatist to purchase the entire silver set to get the one coin he wished, but there was also a rule that coins introduced in mid-year could be purchased separately. In the case of the trade dollar the cost was $1.50 if paid in silver coin or $1.75 in paper currency. As the government was paying out large quantities of minor silver coin at par for paper in the summer of 1873, this was an odd way to do business, but it is likely that Pollock simply did not want to handle paper because it made his accounts more difficult to settle.

At the urging of several influential numismatists, Director Linderman authorized the sale of pattern coins that had been considered for the final trade dollar design. There had been seven designs actually produced for this purpose, but because two of them were virtually the same, only six were made available to collectors. On December 17, 1873, he ordered that 50 sets be struck in silver as well as a special mintage of four pieces in copper from each pair of dies. This was not the total mintage as the dies had earlier been used to strike patterns for official use.

Pollock set the price for the entire set at $18 in silver coin or $30 in paper currency, but specimens could be purchased on an individual basis at a pro rata cost ($3 in silver and $5 in paper). Collectors complained that not only was the price too high, but the differential for paper was hardly reasonable in view of the current monetary situation. Linderman ordered Pollock to lower them to be the same as a regular Proof coin, $1.50 and $1.75, respectively. How many were actually sold is not known, but Linderman had already reserved seven silver and four copper sets for the use of his office. Needless to say, his own collection of pattern coins was quite good.